Questionable Claims, Hazardous Diplomacy By Dario Poli and Mara Lemanis

Questionable Claims, Hazardous Diplomacy

By Dario Poli and Mara Lemanis

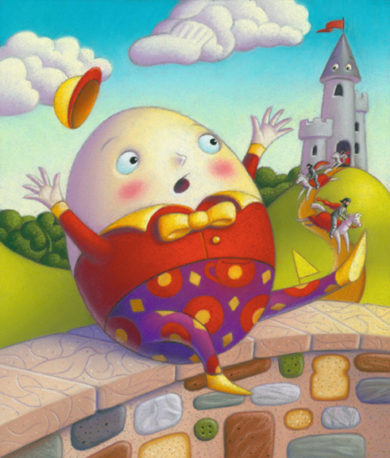

Highly likely sat on a wall and highly likely had a great fall

All the kings’ soldiers and all the king’s men,

Could not put highly likely together again.

Ever since former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter were poisoned by the military-grade nerve agent, Novichok, the British PM, the Foreign Secretary, and numerous EU countries along with the US maintain it is “highly likely” that Russia was responsible for the March 2018 attack in Salisbury.

Issuing a unified statement, the leaders of France, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom all stated that it was “highly likely that Russia was responsible,” requesting Russia to provide complete disclosure to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) concerning its Novichok nerve agent program.

The European Union also condemned the attack, declaring it “takes extremely seriously the UK Government’s assessment that it is highly likely that the Russian Federation is responsible.”

European Council President Donald Tusk said 16 EU countries in all were expelling Russian diplomats and warned that further measures could be taken in the coming weeks and months.

…But we must ask–Where are the internationally accepted norms of diplomatic efforts that are first engaged before such drastic actions?

British authorities have asserted that Russia was highly likely to have been behind the incident but have not been able to provide any evidence.

Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that Russia was “ready to cooperate” and demanded access to the samples of the nerve-agent allegedly used to poison Skripal.

But the British government rejected that request.

The world is holding its collective breath, waiting to see the irrefutable evidence that for the time being does not seem to be arriving from the accusers—neither the UK, the EU, nor the US.

…We only hear the constant expression: Highly likely Moscow behind attack.

The OPCW is the international body banning the acquisition and use of chemical weapons and requiring state parties to destroy existing stocks and production facilities.

And yet state parties have been allowed to produce small quantities of chemical agents for the sake of developing countermeasures to them. This implies that Porton Down possesses samples of Novichok…

Of considerable relevance is the November 2017 address before the OPCW by the UK Ambassador Peter Wilson, praising Director-General Üzümcü and listing his achievements during the year. It is noteworthy that these included: “the completion of the verified destruction of Russia’s declared chemical weapons programme.”

Gary Aitkenhead, chief executive of the Porton Down defence laboratory, told Britain’s Sky News that analysts had identified it as military-grade Novichok, but they had not proved it was made in Russia.

He added, “it is not our job to say where it was manufactured.”

Mr. Aitkenhead did express that “extremely sophisticated methods” were needed to create the nerve agent, and that was “something only in the capabilities of a state actor.”

But what about the consensus–innocent till proven guilty? Is this legal tenet still applicable? Or has it disappeared, without warning, from international laws and legal norms?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 11 states:

Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

What has happened to the legally valid and accepted procedures that legislators, lawyers and police rely on as jurisprudence?

As far back as the sixth century a code known as the Digest of Justinian (22.3.2) proclaims this general rule of evidence:

Ei incumbit probatio qui dicit, non qui negat—Proof lies on him who asserts, not on him who denies.

In accord with the Roman code, Islamic law also holds the principle that the onus of proof is on the accuser or claimant based on a hadith documented by Imam Nawawi.

But in the accusation against Russia and President Putin, this highly important legal obligation has been imperiously and ruthlessly pushed aside.

And still to date we have no highly likely proof of evidence, though Russia’s U.N. ambassador called for a special session of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and requested an open meeting of the U.N. Security Council.

It was not so long ago that the world witnessed the hazards stemming from actions based on unverified assumptions.

The 2003 Iraq invasion stunningly exposed the danger.

Saddam Hussein had neither WMDs nor connections to Islamist fundamentalists. It was the result of his government getting overthrown and his country laid waste that gave Jihadists the opportunity to exploit the devastation.

Anytime intel is scanty or absent, it is certain to become “highly likely” that deadly mistakes will follow.

Even under an ostensibly benign policy, such as America’s “Responsibility to Protect” beleaguered peoples, when information is flawed or inadequate, crises ensue.

In 1992 the US launched a military coalition called, “Operation Restore Hope” in Somalia, a failed state with which it had no diplomatic mission. The result was the downing of Blackhawk helicopters and the killing of pilots, soldiers, and civilians. A badly planned and misunderstood adventure turned disastrous.

The infamous 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion also took place between countries with no diplomatic bodies in place. America’s attempt to derail Cuba’s rival regime ended in the Soviets (Krushchev) planting nuclear missiles there to ward off further attempts at invasion.

The interesting upshot from this did lead to a very cautious and effective crisis management by President Kennedy. Instead of heeding the advice of his Joint Chiefs of Staff, who wanted air strikes over Cuba followed by a ground invasion, Kennedy ordered a naval “quarantine” against Soviet ships entering Cuban ports.

This semantic euphemism—“quarantine”—was a stroke of diplomatic inspiration. Had he called it a “blockade” the implication would have been the existence of a state of war. The softened rhetoric also persuaded the Organization of American States (OAS) to voice their support of the US.

We are reminded that Britain’s most senior chemical warfare expert, Professor Alastair Hay, went as far as advising media it could take “months” to confirm suspicions of a nerve agent. Britain’s top investigators at Scotland Yard also confirmed that timeline.

As Anatoly Antonov, Russia’s ambassador to the US, has said: “The scale of inflicted damage and the preceding information campaign speak of the fact that it had been planned beforehand – simply postponed for the right moment.”

Questions about these dramatic actions before solid evidence has been presented, of course does not absolve Russia as a possible suspect responsible for those abhorrent actions…

But if accusations alone become the basis for retribution, that rationale opens the gate to presumptive acts across the social spectrum. Actionable offenses, such as the expulsion of diplomats, reduce the safeguards of civilization and subvert our legal systems.

Irrefutable evidence is a necessity if the world’s jurisprudence is to be upheld. Short of investigative procedures and valid depositions, what is highly likely is that the global community declines into cycles of distrust, consigned to life on the edge of self-extinction.

Then highly likely will have a great fall…

Biography:

Biography: Mara Lemanis is a literary scholar. Her essays have been selected for 20th CENTURY LITERARY CRITICISM and are included in undergraduate student textbooks in the U.S.

She has worked as an archivist for Historical Preservation and with the IRC, assisting refugees in Oakland, California.

Biography: Dario Poli, artist, illustrator, published author and music composer.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Dario Poli alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Dario Poli and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.