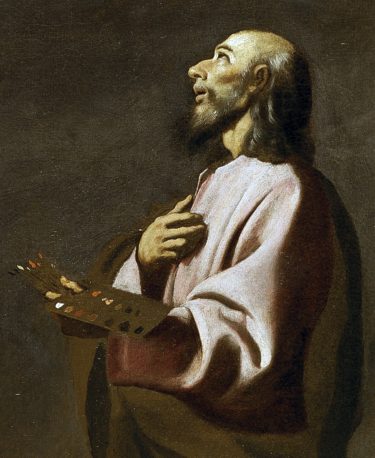

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 130 - Francisco de Zurbarán

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 130 – Francisco de Zurbarán

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) is, besides Velázquez and Murillo, one of the most important Baroque painters of the Spanish Golden Age. He developed a unique visual language in which he combined pure naturalism with modern poetic sensibility. His contemplative paintings therefore became timeless. A number of essays by Cees Nooteboom revealed Zurbarán’s work to the general public in northern Europe.

In his early work there is a Caravaggesque approach with dramatic light, in his later work he is more poetic and personal. Religious subjects are central, such as scenes from the lives of saints, martyrs and monks. The works were often ordered by churches and religious orders. Zurbarán, like his clients, was closely linked to the spirit of Contraformation.

Particular perspective

His paintings were lessons for the illiterate, so they were clear, direct and inspiring. The man from the province of Extremadura remained behind the popularity of the most important painters: Velázquez and Murillo. His work is easy to understand, it communicates directly, there are no double bottoms. He does not like allegories or puzzles, but wants to convey a clear message.

He often worked with an engraving of a sixteenth artist like Dürer. He adapted this to the Spanish context and went back to the essence, in the way of the Orthodox and Medieval paintings. Hence his particular perspective. Space becomes abstract, something intellectual and not something theatrical. It’s not a concrete space but the idea of it, not a reality, but it should look like it.

Spanish Golden Age

The Spanish Golden Age began during the reign of ‘The Catholic Kings’, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. Iberian kingdoms were united and a period of peace and cultural bloom followed that worked throughout Europe. That was also the case with successors Charles V and Phillip II.

The discovery of America only made it better. In the 17th century, Seville was the customs office for the New World. Various artists from all over Europe wanted to come, from Pietro Torrigiano (Florence), Pedro de Campaña (Pieter de Kempeneer from Brussels) to Hermando de Esturmio (Ferdinand Storm from Zeeland).

Major artistic projects were initiated, such as the construction and decoration of the Escorial in Madrid. The foreign artists brought in their own aesthetic language, which was absorbed by the Spanish art brothers. The King’s presented collections of works by the best European painters and sculptors, and this example was followed by the nobility and the monasteries.

To Sevilla

Beginning 17th century, however, the Spanish position weakened as a result of many wars. Areas that had been open to Spanish influence took distance, in Spain itself and in Europe. Nations confirmed their own identity and looked with more suspicion on other cultures and ideas. This became stronger after the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). Spanish painters went on to emphasize their own style, especially after the Council of Trente.

The Council wrote that painted images should serve as a means of communication between people and God. Christ, the Holy Virgin and the other saints did not have artistic value for their own sake, but for what they represented. People’s faith would be confirmed by this and pious behavior encouraged. Therefore, the work had to be simple and direct, and calling on devotion. The bishops watched on it.

In this context, Francisco de Zurbarán could make his appearance on the Sevillian artistic scene. Zurbaran was born in 1598 in a town in the Extremadura between Madrid and Lisbon, Fuente de Cantos. It was already then a disadvantaged region. The young painter went to Seville in 1614. For three years he was taught by Pedro de Villanueva, a painter whose track has completely disappeared.

The crucifixion

When he was 19, he married Maria Páez Jiménez who was nine years older. They got a daughter, Maria, a son Juan – later also a well known painter – and another daughter, Isabel Paula. His wife died shortly after the birth of the last one. Zurbarán was given assignments to participate in altar pieces. Others took care of the sculptures, he did the painting. There is no work from this period anymore.

In 1626 he signed a contract in Seville to make 21 paintings of Santo Domingo / Dominic de Guzmán, for the Dominican Monastery of St. Paul. Three paintings in the sacristy survived: Saint Jerome, Saint Ambrosius and Saint Gregory. Light and dark, following Caravaggio, played a major role.

On the painting The crucifixion he put his signature for the first time. The body of the dead Christ was shaped by the light from a narrow window on a side wall. It radiated serene pathos. It led to assignments from various monasteries in Seville. He could adjust his rates up. And he had to make 22 paintings about the life of Peter Nolasco, the founder of the Order of the Holy Virgin Mary of Mercy. He started the work with some helpers.

The life of Bonaventura

Half of these 22 works still exist and hang out in museums around the world. It can be seen that Zurbarán’s technique was leaping forward. The paintings were hanged in the monasteries as examples for the monks and novices. In the relics chapel came the painting of Our Lady and her holy son. Mary’s head was surrounded with a crown of roses.

The nobility and the rich merchants of Seville also wanted to participate in one way or another. Two major families of Corsican origin, the Casuches and Mañaras, were involved in the construction of the College of Saint Bonaventura. Four paintings from Bonaventura’s life, which the painter Herrera had begun, had to be finished. Zurbarán was called in. He set his own stamp with much dramatic light. The paintings are now visible in Paris, the Louvre, Dresden and Berlin.

The miracle of the Porziuncola

The city council of Seville asked the painter in 1629 to settle with his family forever in the city. He also received the assignment to paint the Immaculate Conception in 1630. At that moment it belonged not yet to the dogmatics of the Catholic Church, but it was already a popular theme, which the local government would like to support.

In addition, Zurbaran received the assignment of the Jesuit fathers and Capuchin fathers in Jerez to paint similar work. Thus came ‘the vision of the wounded Alonso Rodríguez’ and ‘the miracle of the Porziuncola’. In both paintings the holy stands on the bottom half and the heavens on the top. The paintings also show Christ and the Virgin Mary in full glory, in delicate golden tones, surrounded by angels.

Zurbarán’s career was at its peak in the 1630s. In the 1640s he received fewer assignments. He looked at the New World and sent a number of canvases per ship. Because the fleet was hijacked he could whistle for his money. From time to time he searched for local assignments, but he received less and less, we are in the meantime in the 1650s.

With, by now, his third wife he moved to Madrid in 1658, in ruined circumstances. There he passed away on August 27, 1664.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.