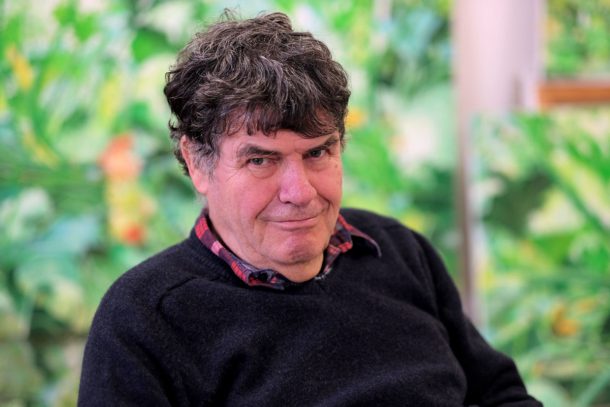

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 116 - Arie van Geest

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 116 – Arie van Geest

I saw Arie van Geest’s work for the first time at the exhibition ‘Masters of Rotterdam’ in the WTC Art Gallery. Not long after, I attended an interview with the artist on the occasion of the recent publication ‘The Broken Promised Land’. It was a packed house at Walgenbach Art & Books. And I paid a visit to Livingstone Gallery in The Hague, which was also showing his work.

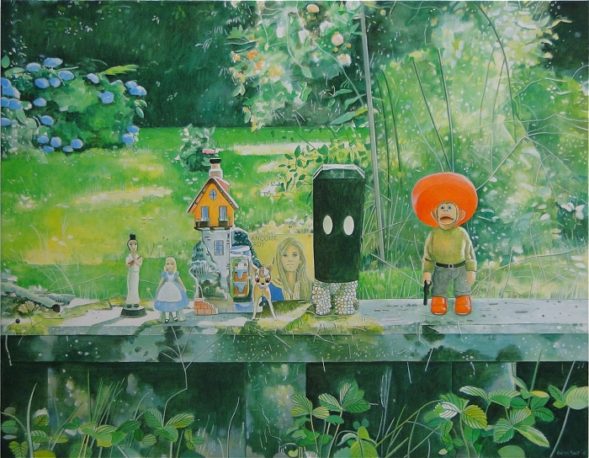

Arie van Geest is a good storyteller, both in word and image. He is a literate man who continuously makes references to themes of famous writers in his artwork. Strips and visual culture in the form of serials play an important role in his work. The main theme of his work is Alice, borrowed from ‘Alice in Wonderland’ by Lewis Carroll with illustrations by John Tenniel.

Light

When I enter his studio in the Drievriendenstraat, I see at right a monumental deer of papier-mâché, besides a blessing Jesus and an automaton, a mechanical boy of almost one meter high. On a closet, under a drawing of Jacob Zegveld of the sixties, there is an extensive collection Pinocchio’s, Bambi’s, Peter Pan’s, Alice’s and other fairytale characters. Van Geest: “The child is the father of the man, so I surround myself with attributes of innocence.”

Top left at his palette table hang some pictures: his wife Berneja, Bob Dylan, Muhammad Ali and a stuffed squirrel monkey with gauze: Mr. Nilsson. The legendary narrative double LP ‘Blonde on Blonde’ from 1966 including the magisterial ‘Visions of Johanna’ was an eye-opener and a decisive influence on the character of his later work. “It’s nice to have traces of the past around me that inspire me.” The studio with three large windows is facing north. “Restful. I have a constant prism of light, sunlight is not intensified. Each studio affects the palette. I’ve had studios at three locations in Rotterdam and in every studio I discovered a different color spectrum. In France, where I spend the summers, the light is different, brighter.”

Serial

Arie van Geest has a long career of nearly 50 years as an artist. His work is included in the collections of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam. He currently makes furore with the series of paintings ‘The Broken Promised Land’. Asked about his theme, he says: You really find it out if you paint more than twenty years. When I went to the Art Academy, I thought naively ‘I’m going to learn to make still lifes and portraits, which I show in a shop and then there are probably people who want to buy it.’ I come from the ‘Westland’, Maasland, a Calvinist enclave, grew up in the period of reconstruction after the war. It was exceptional that I could go to the Academy. At the Academy (now Willem de Kooning Academy) I really only learned two things. In the third year, I was taught by Klaas Gubbels. He made it immediately clear to me that painting is not something you see, but what you think and he then added: painting is a mild form of schizophrenia. That was enough.”

We look at the first painting which he made in 1968 at the Academy. The title is: ‘I am not there’. A simple, pink head in the outdoor area, a somewhat introverted person. You only see a mouth and two eyes. “I made it purely on intuition. It is an illusion, an apparent reality, in the spirit of Magritte’s ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’.” Van Geest taught himself to read at the age of four, although his parents hardly had any books at home. “I found in the newspaper ‘De Rotterdammer’ the serial Don Quixote of Cervantes. That was my introduction to the world of comics and literature. In 1952, Disney made his appearance in The Netherlands with the Donald Duck magazine. Not long after I got in touch with Alice in Wonderland.”

Using your talent

He realized that these stories and adventures were imaginary, mirages. “You come into a jungle-like world of language, a labyrinth of imagination with unprecedented possibilities. All logic is gone. Alice falls down into a rabbit hole and then the adventure begins in a parallel universe. It is a dream that slips into reality. That became the main theme in my observations: the dream that relativizes the reality and reveals new worlds.”

To get something done as painter you need two important things, says Van Geest: content and mentality. “Talent is irrelevant. It’s about what you do with your talent. Believe in what you are. Painting is an excellent way to become yourself. Picasso has shown that it can always grow, even in old age. The first painting in which the dream went beyond reality came from Henri Rousseau, a naive painter. In 1897 he painted ‘The Sleeping Gypsy’. You see a woman sleeping in the desert. The moon shines. Next to her is a mandolin and a remarkable vase. On the other side, there is a lion. You can consider it as the first step towards surrealism. Breton, Apollinaire and Freud played a major role in this movement. It got a visual form by Dali, De Chirico, Max Ernst and Magritte, who once stated: ‘surrealism is the immediate knowledge of reality’.”

Robinson Crusoe

Arie van Geest is not a realist. “I am a representative of the dream.” In the seventies, children play an important role in his work, based on the pictures that Charles Dodgson / Lewis Carroll took of inter alia the Liddell sisters. During a boat trip with the sisters near Oxford Carroll invented the Alice story. Van Geest made a whole series of ‘Alice paintings’ in those years; stilled creatures in an empty space, occasionally in the company of a monkey. Until his thirtieth Alice determined the tone of his work. At one point, we speak of the eighties, he was finished with it. The paintings became more complex. “I started to paint in a different way, expressive but still in soft tones.” A book that went to play an important role in that period was ‘Friday, or The Other Island’ by Michel Tournier, author of ‘The Erl-King’. “Tournier was inspired by Daniel Defoe’s ‘Robinson Crusoe’. He gave it a new twist and went much further. Robinson washes up on the island of Speranza and builds his own territory. He begins a relationship with the island by making love with a trench. After a while flowers with beautiful white lilies appear. A few months later, he is confronted by flowers with black chalices, which apparently implied that also Friday had come to know the pleasures of the trench, jealousy had thus become a reality on the island. The book is an exploration of what it means to be human and what the essence is of survival. Life is finite and eventually we all look in the mirror of nothingness.” The extensive monograph on his work that appeared in 2007, he called ‘Visible Absence’. “Painting is a vehicle that can bring a special poetry. But the poetry of Dylan Thomas, T.S. Elliot, Federico García Lorca, Arthur Rimbaud etc, etc. is of course of a different order.”

Series

On the wall on front of us hang three paintings in progress. Van Geest is actually working on this wall. “It is a quiet setting, a spatial passe-partout. Behind the easel you experience directly the turmoil of the studio.” On ‘Stranded’ we see a Bambi hidden behind a cardboard mask surrounded by the lush greenery while a bright light enters the scene at the top of the canvas, on ‘Desperado’ features a mongoloid monkey in red patent leather shoes and sporting a sombrero in a concrete environment full of cracks, mosses and fungi and ‘The Future’ shows a metal robot for a labyrinth of branches and foliage. The paintings represent three diverse states of mind. “The first, Bambi, ‘how do I go on?’ The second, the monkey, represents the modern madness the world is facing, and the third the technology that is inevitable.”

Regularly series arose in Van Geest’s oeuvre. In 1984 ‘Tableau Mourant’, 98 watercolors. A recording of the destruction of an individual. The series was exhibited in 1986 at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, then in the Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh and was bought by the same museum in 1987. The series is based on the painting ‘The end of the day’ that Van Gogh painted after a work by Jean-François Millais.

In 1999 he created the series ‘Desolation Row’, a series of 70 watercolors. A parade through the gentle madness of fantasy. The title he took from a song by Bob Dylan. There is a figure emerging – an alter ego of the painter – based on a character from ‘The Cripples’ (1568) by Pieter Brueghel. Between 2009 and 2011, came the twelve-part series ‘Alice (high, low and in between)’. The publication which appeared on the series, begins with a quote from Bob Dylan: ‘Winter goes into summer, summer goes into fall. I look into the mirror, don’t see anything at all’.

The sleeping giant

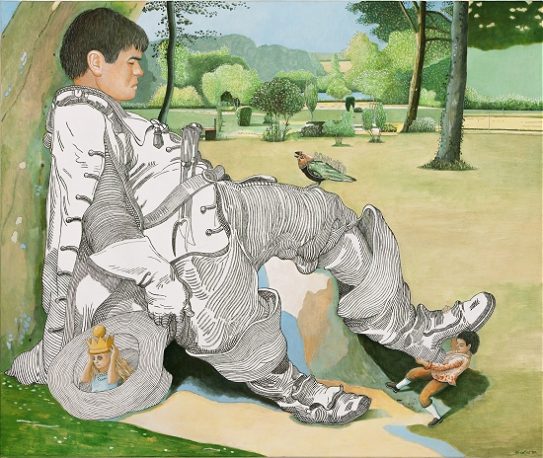

In late 2010 Van Geest was faced with a serious problem: prostate cancer. In january 2011 he was operated. The result was good but he then faced a prolonged fatigue that led to a sabbatical of almost a year. For months he studied somewhat melancholic the garden adjacent to his French summer residence: the early spring, the birds, the compact green of summer but above all the ever-changing light. In late 2011 there came an end to the deadlock and he resumed painting. “The first painting that I created I called ‘The Sleeping Giant’. You see a sleeping giant leaning against a tree in a park-like setting, based on an engraving by Gustave Doré. A bird on his left knee. Alice, who herself puts a crown on the head, is in his hat lying in the grass beside them. A bloody dwarf is lashing his left boot. In retrospect , it is the overture of the series ‘The Broken Promised Land’ which at that moment consists of 50 paintings.”

Private wonderland

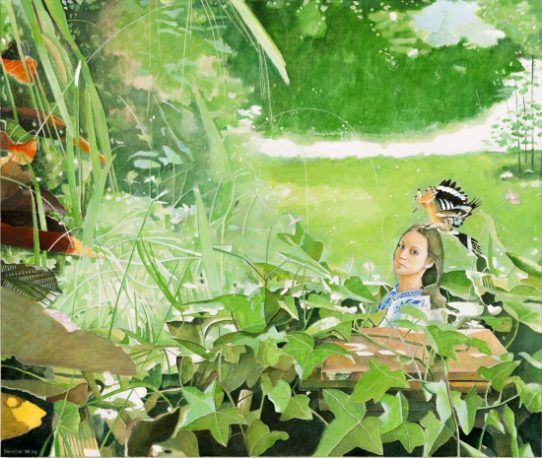

The summer after he painted ‘The little grace’. You see the same figure again as a dwarf with giant ears behind a pile of tiles in a tangle of plants. Then the can with ‘heteronyms’ was put wide open: Pinocchio, Ganesha, Hanuman, Berneja his ladylove, Moana his granddaughter, Anubis, Bambi, a severely disabled Dopey, a Filipino dog covered with hundreds of tiny shells that imagines the role of God and of course the inevitable Alice. The specific summer light that largely determines the character of the garden, is the unifying factor.

Why the title, ‘The Broken Promised Land’? “It is my private wonderland but actually as well a panorama of today’s world, which is paradoxical and can be extremely gruesome. I am a desperate optimist, a contradiction in terms. The tone in the series shifts over time. In the mid-seventies I saw the opera ‘Einstein on the Beach’ by Philip Glass. That lasted five hours. The decor changed painfully slow. It was an eye-opener, just like ‘Blonde on Blonde’ at the time, a key moment and it encouraged me to work in series. The images glide slowly into each other, are merging so to speak, it’s a comic book, a serial. The series ‘The Broken Promised Land’ I consider a victory over the uncertainty and creating it I experience as a stimulant intoxication. Technically the making goes without a hitch. All kinds of idiocy / schizophrenia lurking in me, I can give a place.”

Sports fan

Besides painter, Van Geest was 29 years teacher at the Willem de Kooning Academy. “When I began at the Academy conceptual art was emerging. But I chose from the very beginning for the narrative. Lewis Carroll vs. Celine, The Songs of Maldoror of Lautréamont, the first literary surrealistic quest, a gruesome labyrinth formed by the specific darkness of the dream, Paul Auster, Philippe Claudel, Michel Tournier, Vladimir Nabokov, Gustave Flaubert, Gerard Reve, they were the beacons where I focused on. So I am greatly indebted to literature.”

Finally, does he have a philosophical conclusion? “Essentially, I own only one thing really: my life. Everything is connected to everything. I’m also a big sports fan. Sometimes sport delivers the same emotion that you can find in art: flying Epke Zonderland, the gymnast, Jan Janssen, in the sixties, the first Dutch tour winner. I am and remain a very patient but fervent Feyenoord supporter and saw a few years ago Robin van Persie’s finest goal floating in the goal in the match against Spain. ‘Free as a bird’: the essence of both life and art, that was a touching moment of immense happiness.”

Images: 1) The Sleeping Giant, oil on canvas, 100 x 130 cm, 2) The scaffold, 2012, oil on canvas, 100 x 130 cm, 3) Lost, 2012, oil on canvas, 4) Berneja (Mandorla), 2013, oil on canvas, 100 x 130 cm, 5) The Offer, 2014, oil on canvas, 70 x 90 cm, 6) Grace, 2014, oil on canvas, 85 x 105 cm, 7) Songbird (Moana), 2015, oil on canvas, 8) The Art of Painting, 2016, oil on canvas, 70 x 90cm, 9) Small Wonderland, 2016, oil on canvas, 100 x 130 cm, 10) Arie van Geest, photo Arie Wapenaar

http://www.livingstonegallery.nl/

http://ifthenisnow.eu/nl/verhalen/de-wereld-van-de-rotterdamse-kunstenaar-21-arie-van-geest

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.