World Artists and their Story, 19 - Antonio Gaudí

World Artists and their Story, 19 – Antonio Gaudí

Antonio Gaudí was at the cradle of the Catalan Art Nouveau. He was one of the founders of organic architecture. He is best known for his Sagrada Famiila, the cathedral in Barcelona which is ongoing since 1883 and where he is buried.

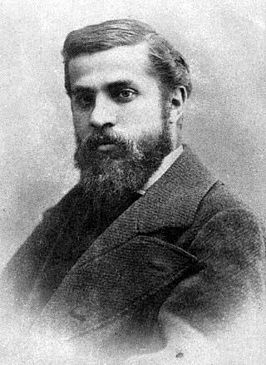

Antonio Gaudí, short for Antonio Plácido Guillermo Gaudí i Cornet, was born on June 25, 1852 in Reus (Taragona) as the son of a copper smith. Because of his rheumatism he had to stay at home a lot and when he went out, he had to be transported on a donkey. All his life he suffered from rheumatism.

El Arlequin

Antonio was a good student. At the age of 11, he entered the school of the Fathers Escolapios in Reus. There he also gets art class. In the fifth class of the gymnasium the local newspaper El Arlequin places – to his delight – drawings of him. It doesn’t matter that the newspaper has a circulation of twelve copies and is written by hand: it had become public. Then he goes to work on the sets of the school theater.

At 17 he receives his high school diploma and moves to Barcelona, to the preliminary class of the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Barcelona. During the study, he is 18, he is involved in the restoration project of the Poblet monastery. He can design the armor for the abbot of the monastery.

He got the taste of architecture. When he was 22, he followed for three years an architecture study at the Escola Provincial d’Arquitectura in Barcelona. He makes many designs, including a gate for a cemetery, a design of a hospital and a jetty. To pay the rent, he works with architects.

Gothic Revival

Among others, the office of Josep Fontseré and that of Francisco Paula de Villar. Along with Villar – who later would begin the construction of the Sagrada Familia – he worked on projects in the Montserrat monastery. His ideas he took from books. He was initially quite traditional. But at one point he needed his own style. The climate in Barcelona was ready: there was a great openness and everyone was looking for something new. The view was across borders.

Gaudi studied the French Gothic Revival. He was interested in social ideas. Many others in Catalonia had become interested in it. It fit a need to show again respect to Catalonia, that had lost its independence from the Spanish central authority. Gaudi was critical of the church, which earned him sympathy.

On his 26th, he’s about to graduate, he received his first public commission. He can design a streetlamp for the city. The following year he sees his lanterns placed. Next assigment is coming up: a design for a shelter for the workers of a factory. Together with the workers cooperative of Mataro he works on it. The design gets praise. It is shown at the Exposition Universelle, the World Fair of 1878 in Paris. At that time, he just got his architecture degree.

Eusebi Güell

A few years later, he is 30, he begins to cooperate with the architect Joan Matorell. They have the same focus, that of the neo-Gothic architecture, which also has a political flavor: it is an expression of the desire for Catalan autonomy. Gaudi makes trips to Catalan historic sites. This he does with organizations like the Asociación de Arquitectura de Catalunya and the Asociación Catalanista d’Excursions Científiques. They visit gothic cathedrals and Moorish buildings.

It affects his work. The following years he began to work on Casa Vicens. Five years he’s working on it. The ornamentation stands out: it is a synthesis of Gothic and Mudejar elements. Gloves shop owner Esteve Comella walked past and continued to be surprised: who the hell had designed this? He had to know more.

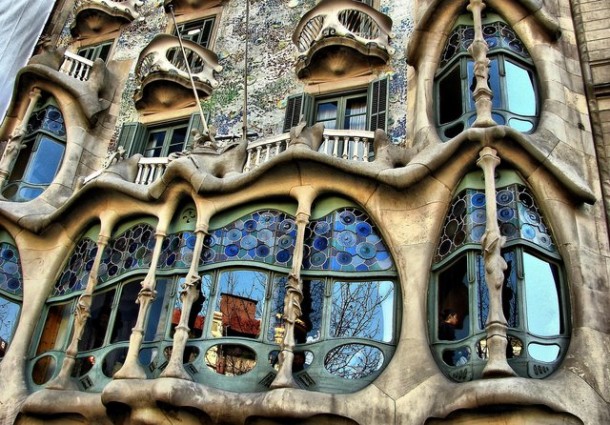

An appointment was made and Gaudi was invited to work on a new project, in one of Barcelona’s main streets. It had to be a city palace, in the style Güell had seen. In three years time Palau Güell was designed and built. In 1889 it was finished. Güell was more than happy. Other palaces followed: Casa Calvet was completed in 1900, Casa Battló in 1906 and Casa Milà, La Pedrera, in 1910. Every time Gaudi dared to go one step further in his experiments with organic elements and ornaments. The dripping shape was introduced.

Park Güell

In 1900 Güell commissioned Gaudi to design a park in the northeast of Barcelona. It was an area of 15 hectares with a dense pine forest. On a trip to England Gaudi was impressed by the landscape parks. Such a park he wanted to make, but with his interpretation. He made Park Güell, an earthly paradise with a giant snake and benches of broken porcelain which was fitted together in mosaics, in the form for example of a salamander. The apple, the forbidden fruit of paradise, got a metamorphosis in a rendez vous place, and there was a porter’s lodge, a colonnade and later a small Gaudi museum.

Meanwhile Gaudi had taken over the design and construction of the Sagrada Familia church. Francisco Paula de Villar had not gone beyond the building of a crypt. The ideas and designs which Gaudi had developed, he began to apply for the design of the Sagrada Familia. He wanted to have a good grip on the implementation and started training the workers himself. He always wanted to be informed, about everything. Slowly the building progressed. The Barcelonians watched with open mouths. What happened there?

A hermit

Gaudi was day and night on the construction site. He lived as a hermit for many years. The church was slowly progressing. On June 7, 1926, he is 74, he left late in the afternoon the workplace to get some fresh air and to go to confession. Totally engrossed in thought he was hit by a tram. Barcelona tram drivers were notorious for their driving style. They rode fast and pushed intrusively their way through crowds. He is unconscious and – because of his ragged clothes – taken to the hospital for the poor. Then the nursing staff learns that it is Gaudi, the architect of the new cathedral. He is moved to the private room. Three days later he dies. The funeral was almost a state’s affair. Hundreds of thousands accompany him to his final resting place. He is buried in the crypt of the church.

The Franco regime did everything to work against the cultural identity of Catalonia, and Gaudi was an exponent of it. The construction of the Sagrada Familia progressed therefore very slow. But in the sixties and seventies, there was a resurgence of Catalan self-consciousness. And Gaudi’s work was part of it.

Hundredth death anniversary Gaudi initiation cathedral

But not everyone was as enthusiastic. George Orwell wrote in his Homage to Catalonia about the Sagrada Familia: “Unlike most churches of Barcelona, it remained undamaged during the Revolution. It was spared because of its ‘artistic value’ they say. I think it reflected the bad taste of the anarchists that they did not blow it when they had the chance.”

Salvador Dali, however, had great praise and spoke of ‘Tapas Art’. Pablo Picasso on the other hand, didn’t like it at all. He wrote in 1900 in a letter to a friend: “In my opinion Gaudi and the Sagrada Familia can be sent to hell.” Maybe Gaudi himself was also a little bit to blame. As his fame increased, he became stricter in the interpretation of the Catholic doctrine – on his last outing where he fell under the tram he was on his way to confess. In politics he became more and more anti-libertarian.

Other architects continued his work on the cathedral: Francesco Quintana, Puig Boada and Lluís Gar. The sculptures were continued by Jaume Busquets and facades by Joseph Subirachs. In 2005 the building was declared a UNESCO World Heritage. At this time, the nave is covered. The whole cathedral is expected to be completed in 2025. The festive inauguration is scheduled to tale place on the hundredth anniversary of Gaudi: June 10, 2026.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.