Financial markets hitting Spain

When renowned academic Nouriel Roubini said that Spain, not Greece, was Europe’s No 1 problem, he created a stir. He also created a problem for an old university friend, Spain’s economics secretary José Manuel Campa, who has since been forced to work round the clock to reassure international investors that Spain is a “solid” country and should not be compared to its fellow Eurozone struggler.

When renowned academic Nouriel Roubini said that Spain, not Greece, was Europe’s No 1 problem, he created a stir. He also created a problem for an old university friend, Spain’s economics secretary José Manuel Campa, who has since been forced to work round the clock to reassure international investors that Spain is a “solid” country and should not be compared to its fellow Eurozone struggler.

Roubini, the man who foresaw the sub-prime crisis, raised the heat on Spain, where the financial crisis has left nearly 20% of the workforce unemployed as the country’s model of growth based on a construction boom has unravelled. The past week has forced up interest rates on Spanish bonds and the share prices of profitable companies such as Banco Santander have dropped by 13%.

Putting on a brave face, Campa told the Observer: “Markets react drastically, we’re better off this week than last before we announced our budget cuts.”

The country’s four million jobless are certainly not better off. Far from Madrid’s bureaucratic centre, or the elite gatherings of Davos, thousands live on €1,000 (£870) a month. Service sector and office workers have their salaries capped at this level as employers know that, with 18% unemployment, they are unlikely to rebel.

“We’re all taken by the balls – we can be forced to go at any minute and you don’t know if you’ll find anything else,” says Maria, an employee of a fashion chain in Barcelona. “They give me three-month contracts, so if they want to get rid of me, they won’t have to pay me. I spent one year unemployed, without being able to go out.”

An hour’s drive south along the Mediterranean coast, schoolchildren in Tarragona do not go on school trips as their parents can’t afford the €12 cost. “You can see some children buy their textbooks at the beginning of the month, after pay day,” says a teacher.

Further south, in Jaén, “where nothing, is moving,” Javier Díaz’s family ring constantly for advice as they seek to follow him to Madrid where he has found work as a taxi driver. But opportunities are scarce even in the capital. “Things are going to get worse as soon as people stop receiving their unemployment benefits,” he says.

Every Spaniard seems to know somebody caught in the real estate bubble burst. Cheap credit and the arrival of about six million immigrants over the past decade allowed the construction sector to become the country’s leading economic driver, representing as much as 25% of gross domestic product at the peak of the boom. Villages on the Valencia coast, dependent on fish and agriculture for centuries, started building state-of-the art glass buildings in a country that has always been more labour- than capital- intensive.

Properties worth €1m stretch along a coast that, far from Madrid and Barcelona, rarely generated much wealth. People on €1,300 a month owned BMWs and couples making €30,000 a year bought €500,000 homes.

Campa and economy minister Elena Salgado are working to help the unemployed, and to make services and tradable goods fill the part of GDP that construction once accounted for. “This won’t be a good year for jobs, but at least the rate of job destruction is slower,” Campa says.

As he spoke last Friday, financial markets kept hitting Spain. Although it has not had to spend billions to bail out banks, the country has lost credit in the international community, which is “looking for the next Greece, and looks at the numbers, instead of politicians talking the talk”, says Gary Jenkins, at Evolution Securities in London.

As he spoke last Friday, financial markets kept hitting Spain. Although it has not had to spend billions to bail out banks, the country has lost credit in the international community, which is “looking for the next Greece, and looks at the numbers, instead of politicians talking the talk”, says Gary Jenkins, at Evolution Securities in London.

Last week Spain announced higher taxes and draconian cuts to the deficit from a staggering 11.4% of GDP to reach the EU target of 3% by 2013. But markets have been unimpressed and now demand a record $183,000 to insure $1m of Spanish debt, twice as much as Britain.

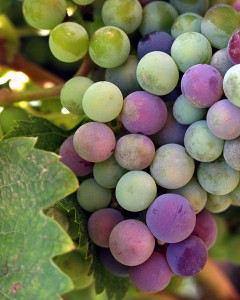

Alien to the London-based derivative markets, most Spaniards are suffering the consequences: winegrowers in the Priorat area are idle as the prices for grapes are lower than the cost of harvesting them. “Many winery owners are selling out – they can’t afford to pay for the loans,” says Rafael de Haan, owner of Bodegas Albanico, a wine exporter. “Some are selling top-quality wine at wholesale prices – and in wholesale amounts.”

But while the wine may be cheap, with some economists saying Spain won’t recover until 2016, there is not much to celebrate.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Simon Schönbeck alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Simon Schönbeck and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.