World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 476 - Jan van der Pol

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 476 – Jan van der Pol

Jan van der Pol (1949) is a versatile artist from Amsterdam. He practices his profession with a lot of energy. He regularly discovers new areas where he unleashes his imagination. He is also a good storyteller. I experienced this when I recently visited him in his home and studio on one of the quays in Amsterdam Oud-West.

I first saw his work at Art Rotterdam 2024 in the Creman & De Rooij stand. I saw several geometric drawings there that were not entirely correct and which he therefore also refers to as quasi-geometric drawings. He was also – alongside Maaike Kramer, Peim van der Sloot and Mónica Mays – one of the selected for the NN Art Award 2024. Their work was on display in the Kunsthal for almost three months. About 100,000 visitors attended.

African sculptures

In the beautiful building I first have to climb a fairly steep staircase. I get a short tour of the living room with paintings by fellow painters on the walls. On various tables I see African sculptures – grouped by cultural area. From Burkina Faso, Togo, Cameroon and Tanzania, among others. These are beautiful sculptures and it is striking how each cultural area has a specific style. He has collected them over the years.

We walk further, to his studio in the attic space. It looks clear and neat. In terms of shape, it is somewhat similar to the Saved House (het Behouden Huys) on Nova Zembla. There is a velum in front of the skylight to block out the light. The window to the street side is closed with window doors. On the right his large paintings are lined up, on the left I see a long row of his drawing books – with one or more drawings every day – and on one of the tables there is a square board with different colors of paint.

Rose nursery

Jan does not originally come from an artistic background, but as a boy he felt an irresistible urge to get into it and eventually he found his place, he says. Jan: “I grew up in the province, my parents had a rose nursery in Aalsmeer. Schiphol was a little further away. From my bedroom window I saw an industrial landscape, beautiful chimneys, large greenhouses. Around us were polders intersected by ditches, it was a man-made landscape. My parents were very Protestant. They loved choirs and music that had to do with faith. My father was originally a carpenter, but due to the bad economic situation in the 1930s he switched to flower growing. I lived there until I was 14/15.”

Jan did not feel completely comfortable in this down-to-earth, no-nonsense environment. In the encyclopedia he saw two reproductions of Egyptian statues with art from the ancient Egyptian empire, including a statue of a king. “Someone(s) made that with their hands!” he realized. “That gave me comfort. I want that too.”

A crazy idea: becoming an artist

When he was 12/13, he visited the Rijksmuseum and saw Rembrandt’s painting The Staalmeesters. That made a big impression. “’This is how it should be!’ I thought. I understood it too. I’m going to do that too.” He was 16 then. He took the entrance exam for the Applied Arts School (later the Rietveld Academy). A few days later he received a letter at home stating that he had been admitted. “Fantastic.” For his parents it was a crazy idea: becoming an artist. After all, Jan was the doomed successor to the rose nursery. But his father didn’t stop it, he gave his son space.

In a preparatory year he was introduced to all departments of the Applied Arts School. “At the end I had to choose a department where I would stay longer and chose the Goldsmiths department. Because my parents respected gold and silver. But after a while I also started taking all other lessons, from graphics and painting to figure drawing. I thought everything was fantastic. I was always a reader. When a translation of Franz Kafka’s Der Prozess came out, I bought it. The book made a huge impression. And it made me laugh too. What wonderful summaries. I also read his book America. America reminded me of Buster Keaton, in the beautifully funny passages. I also started going to the cinema to see films. I soaked it up like a huge sponge. I felt like I was finally among normal people.”

Painting class

Many of the teachers were painters. Jan was part of the painting class with his fellow students. “We learned a lot from Melle. Awesome! Nice man too. When we almost graduated in 1969 after four years, Henk Broer, draftsman and painter, and Ap Sok, the graphic artist, said: ‘Jan, go to the National Academy (Rijksakademie). There you will receive a scholarship, so you can live wherever you want in the city. There is a wealth of painting materials.’ Arie Kater was a professor there. On the Stadhouderskade there were a group of cabins, workplaces for Prix de Rome candidates. I could use that for two years. I was having a great time, I worked really hard.”

When he completed the Rijksakademie in 1971, he was an independent artist. He graduated with honors from two academies. To this day, he remains in touch with several people from his class, the first of whom graduated in 1969.

To work

The first years were very difficult. “Two days a week I went to work for a friend who built and restored instruments. I did technical things. Many tools had to be devised and made. I had that skill from home. There I had walked around in the boiler house near the machines. My uncle was the machine man at the nursery, he was friends with the blacksmith. I was right on top of that.”

He got in touch with a gallery: Kunsthandel Lambert Tegenbosch from Heusden. For a while he received an amount every month from the gallery so that he could continue working. Charlotte van Pallandt was one of the other artists at Tegenbosch. “I regularly heard from Lambert: ‘I have sold so and so much, you will still get money from me’. Tegenbosch had a good formula. He also wrote a lot. He bought at auctions and curated exhibitions in the upstairs space of the gallery. Solo exhibitions by young artists were held in the downstairs area. Interested parties regularly came by, including pharmaceutical companies and directors of the company Organon from Oss, who also bought.”

Tegenbosch after a while brought him into contact with the Wetering Galerie of Michiel Hennus. “I worked with him for 30 years. Not an unpleasant word about him. Every year and a half he organized an exhibition that also included my work.”

Prints, drawings, paintings, photo collages, etchings and linocuts

Jan van der Pol made prints, drawings, paintings, photo collages, etchings and linocuts. In the early 1980s he developed the habit of making a number of drawings or watercolors in books every day. They became a kind of diaries that, to use his own words, are full of: “a kind of analyzes of metamorphoses that had taken place in paintings and turned into visual reflections, which could then be used as a starting point for painterly formulations.”

The titles of the – more than 100 – books are not unimportant. This also applies to the titles of the large paintings. He has even grown fond of it. There is a list of titles on a piece of paper.

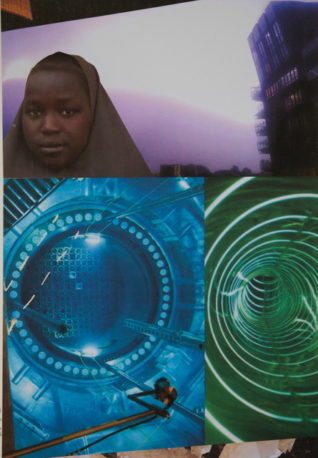

Book no. 64, MEADOW, (colored) pencil and photo collage, 42cm × 29cm

Book no. 68, Spark Plugs, colored pencil and gouache, 52cm × 39cm

Book no. 72, Then it should be like this, colored pencil and gouache, 42 cm × 29 cm

Book no. 74, Dibbets Never Did This, colored pencil and gouache, 42cm × 29cm

The pictures are striking in color. In any case, color plays a leading role in the work as a whole; it is a wonderful tool for achieving visual immediacy.

They are disruptive representations of urban landscapes and buildings – often based on photographs – in combination with abstract elements, sometimes even in labyrinthine drawings consisting of one line, based on the idea of A Walk of Life.

He completed the linocut project IUOEYA BFG X ZNQD VCSP KWTRL HMJ in 1999. “It started with a woodcut from the booklet De Hieroglyphica by Horapollo from 1550, published in Paris. That booklet contains 195 illustrations of texts written around 300 AD. originated in Egypt near Alexandria. The texts – sometimes very short – describe how all kinds of things can be depicted and the small woodcuts show this. This had become an important book in the artists’ studios in Western Europe in the 15th century. Attempts were made to canonize imagery.” Over a period of one and a half years he cut 195 images, the entire project took five years. The images emerged from his imagination and were a kind of encyclopedia of image components that had been used in his oeuvre over the years. There are abstract and figurative motifs on display, portraits, landscapes and architecture. Michael van Hoogenhuyze translated the texts from Greek and Latin into Dutch. The composition of the prints was placed above the text as one long ribbon. Image and text form two parallel coincidental worlds, but when they meet they are difficult to separate.

Key works

He has several key works, the first of which he mentions is ‘Magazijn Memoria’.

In 2002, something new emerged from the enormous graph folder IUOEYA. “I called the author/poet Atte Jongstra. At the time he described his work as ‘Opened up work’ and saw similarities in approach with my work in associating different things. We had a fantastic back and forth conversation. I will send you proofs of 18 prints, let your mind wander. After a few weeks he called back and read three poetic texts. ‘Is that something?’ “It’s hit the nail on the head.” It led to 52 prints with a poetic text, ‘Magazijn Memoria’, one of his most beautiful collections of poetry. Some poems very compelling. The De Roos Foundation has turned it into a beautiful book.”

In 2004, the BKVB Fund hosted an exhibition of the loose pages from the Magazijn (warehouse) ‘Memoria’. Both artists had, as it were, unleashed their memories on each other. Memory is depicted as a warehouse, full of extremely diverse impressions.

The second key work are paintings that were created when the communist system in Central and Eastern Europe collapsed. “I worked with photos – also on the TV screen – of striking images, including those of prison camps. It led to a collection of very different paintings. At the same time I read intensively books by, among others, Isaak Babel, Daniil Kharms, Anna Akhmatova, Alexander Blok, as well as work by Gogol, Nabokov and Zinoviev. I have also traveled a lot in Central Europe.”

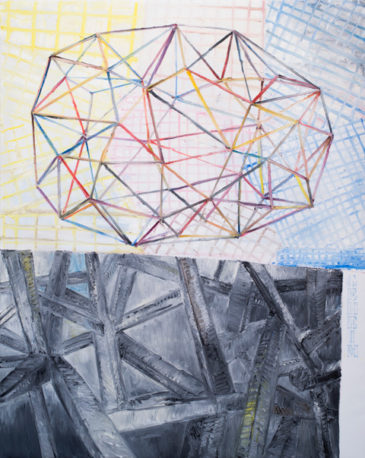

A third key work is the first work of the explosion of 2019, the painting ‘The Angel Gabriel, aka KING KONG’. In 2019 he had an exhibition at the Morat Institut in Freiburg. Following that exhibition, he felt the need to put a number of things on hold due to emerging doubts. “I was hesitant to translate human intention into non-figurative images. I thought I needed figurative images for it.” He combined these images in collages that apparently did not have much to do with each other. See also the tabloids ‘For our nation’ and ‘A NEW DAY’, which I receive from him. A project together with Joost van den Toorn, Tom Thijsse and Atte Jongstra, among others. In the autumn of that year he put his doubts aside and produced a whole series of new paintings. “It was a shocking experience. A fantastic world opened up. The fact that Covid was around made it absolutely wonderful. In the years 2020-2022 I was able to work with complete concentration. It came at just the right time. I made ±200 small paintings with a size of 40 x 45 cm and a series of large paintings with a maximum size of 200 x 150 cm. In the years before that I made a maximum of 13 to 15 paintings per year, which had a long incubation period. I did work in the drawing books every day.”

What is his experience with the art life?

“I met interesting people. To this day I am in contact with a number of people from the Rietveld era. I was in a fairly large group. Graduated in 1969. That year drugs started to play a role. Eighteen months later, four of that group had died of an overdose. I preferred to stick to a shaggie (self-rolled cigarette) and a beer. I had no need for mind altering drugs.

Things went very well with some of my friends/year-mates. Paul Husner went to Indonesia and made beautiful work there, Tom Thijsse, graphic artist, went to Japan and Finland and makes beautiful work. He was also a good teacher. Others went to the United States. I also started teaching, painting and drawing, two days a week at the Royal Academy in The Hague. I found teaching very rewarding. Getting to know many special students.

Then you have the combination of art and business. Jiri Svestka curated exhibitions in his gallery in Prague with works by a number of artists, including me. In between he also hung one or two Warhols, with a price tag of six zeros. I thought it was fun but also alienating to hang it between works costing 12,000 euros. In that setting it is no longer about the meaning of a work. That part of the art world is about money, a kind of stock trading.”

Finally, what is his philosophy?

“It is customary for work to be signed. In African art, however, signing is a futile matter, it is about the sculpture, the maker is important but his ego is not. I understand that well. J.M Coetzee wrote the book ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’. A very compelling book that seems to have been written by an anonymous person. I really liked that. This made him free in a sense. The same applies to me: my work must be in the spotlight, I don’t have to.”

https://www.janvanderpol.info/

https://www.instagram.com/janvander.pol/

https://www.instagram.com/creman.de.rooij/

https://inzaken.eu/2024/05/17/een-nieuwe-ontwikkeling-in-het-werk-van-jan-van-der-pol/

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.