World Fine art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 472 – Margje Bijl

World Fine art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 472 – Margje Bijl

At the opening of her solo exhibition ‘Tache de beauté’ (Galerie Move, The Hague, 2004) and the accompanying publication ‘Marg, the stain champion’ (Marg, de vlekkenkampioen), Margje Bijl received a photocopy of an intriguing lady. She was bent over, the support of her left hand keeping her from bending all the way. She had black curly hair. In a flash Margje recognized herself. She looked at it again and then it sank in, this was different.

Margje Bijl – who I speak to in her studio in the beautiful Oosterbeek estate on the border of The Hague and Wassenaar: “I thought that the person who gave me the photocopy had edited a self-portrait in which I was wearing a dress with similar sleeves. She said nothing about the mysterious woman or the artist, only that it was from a weekend newspaper supplement. The copy was so blurry that for a long time I thought it was an oil painting. A friend had said that the lady belonged to the Pre-Raphaelites, but I did not recognize her in their paintings. Image search did not exist yet.”

Margje let it go and continued with her own art practice in The Hague. “I made installations inspired by the myth of the beauty ideal and the rituals that accompanied it. With my stain drawings I offered another world, a projection screen for the subconscious.”

The Pre-Raphaelites

Margje Bijl decided to continue her research into the mysterious woman when she saw posters everywhere in 2009 of a large retrospective exhibition in the Groninger Museum by John William Waterhouse. He belonged to the Pre-Raphaelites. British artists in the Victorian era, mainly painters, who opposed the academic art as prescribed by the Royal Academy of Arts. They wanted to return to the simplicity that existed among the artists living before Raphael. They aimed for simple compositions and a precise, realistic working method. The movement began in 1848 when Dante Gabriel Rossetti and some friends founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood society. A few years later Waterhouse, William Morris and others joined.

“While Googling ‘Waterhouse’ I found a second photo from the same series. From that moment on I was able to find a lot online. Jane Burden Morris lived from 1839 to 1914. As the wife of William Morris and as the muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, she also contributed a lot to the movement.

Jane and I don’t just have a physical resemblance. Things happened in her life that are also a theme in my life. This is how we both became muses and lovers of an artist 11 years our senior. Rossetti often depicted Jane as a mythological goddess and elevated her to a new ideal of beauty. She was not a frail doll, as was popular in Victorian times, but a lady with androgynous features. And that is precisely what caused her enormous appeal, which continues to this day. Rossetti had the photo series made of her. Sipco Feenstra has photographed me for years. I like to use his photos in my work because we both didn’t know there was a resemblance yet.”

Reflections on Jane Morris

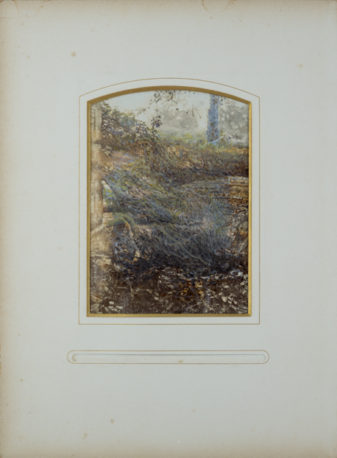

With the discovery of Jane’s life story, Margje’s project ‘Reflections on Jane Morris’ was born. She went to England to investigate further. She first saw the original photos in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in an album of prints. “I was quietly leafing through it until I saw that one, WOW, it came in!”

“The Pre-Raphaelites are still very popular, especially in England, so there is a lot to be found in archives and museums. In the Netherlands, William Morris is best known for his wallpaper patterns and as the founder of the Arts & Crafts movement. The Industrial Revolution was happening in the 19th century and William Morris hated it, he was against machines. He was into the craft, the materials. He and his friends wanted to make art accessible to everyone. That caught on.”

Margje visited the former homes that have been preserved and converted into museums, such as Kelmscott Manor (near Lechlade, in Gloucestershire) and Kelmscott House (in West London), where the William Morris Society is now located. “In the first house where William and Jane lived with their two daughters (‘Red House’ in Bexleyheath, South East London), all their friends played a role in furnishing the house. They made stained glass, tableware, furniture and wall decorations, among other things. That grew into the company Morris & Co, where Jane was the manager of the embroidery department for 20 years.”

Back in the Netherlands, Margje made a series of hair drawings inspired by Jane’s portrait. These were on display during the solo exhibition ‘Reflections on Jane Morris’ (Galerie de KunstSuper, Rotterdam, 2010). Just like ink-edited photos, other pencil and ink drawings and paintings. “These were first experiments, everything was still very exciting. I liked creating confusion, when I draw Jane I sometimes end up with myself and vice versa.”

A Memory Palace of Her Own

During the second trip, Margje took a number of photos in the former homes with her then boyfriend Hein van Liempd. The series was exhibited in 2014 at the William Morris Gallery in London, where William grew up, in honor of the 100th anniversary of Jane’s death. “I don’t want to look like her with long dresses and a bent-over posture. I wonder how I can complement her life as a contemporary artist.”

19th century photography

Margje delves into the various techniques of 19th century photography. “I made a number of works with anthotypes. You smear the paper with an emulsion of flowers, for example, after which you place it in the sun with a transparent negative for a number of days or weeks. It produces a vague image that I printed in antique books. A few years ago I made a number of wet glass portraits with the photographer Gerjo te Linde. That is the same technique used to create that photo series of Jane. During my recent solo ‘Looking for Janey’ (Pulchri, The Hague, 2024) I exhibited two large prints from this session. We are going to do a second session soon where he will teach me the technique. I would like to experiment with the emulsion.”

Image 7

Life’s work

The entire project is her life’s work, says Margje. “I want to find out who Jane Morris was and from the beginning I noticed that there are many layers to it that other people also find fascinating. Even if I am not directly working on Jane, my work has a place within this context because I am working on a double biography. With various projects I depict how our lives are connected. That will keep me busy for the rest of my life. I have to do it, to honor Jane. That gives me extra strength and focus. She makes me bigger than I am.”

Cultural heritage

In England, the cultural heritage of the Pre-Raphaelites is kept alive by, among others, the Pre-Raphaelite Society. “In 2019 they organized the conference ‘Pre-Raphaelite sisters: making art’ where I showed a video work. A curator offered me a solo exhibition and I started developing my own ‘Jane Morris Museum’. We wrote about it in the magazine PRS Review, which I still enjoy writing for.”

Margje received recognition that she is now an expert in the field of photography around Jane Morris.

“I have found my niche. Last year I discovered a ‘new’ photo. In the archives it was mistaken for a different photo, but I immediately saw the subtle difference.” Margje was able to place it in a broader context. “I know which other museums have work from that same series. I notified them all to connect all the pieces of the puzzle. The photo is now online. I hope to find more photos of Jane.”

Does Margje have a key work?

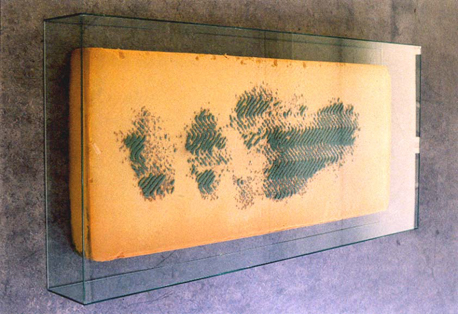

She has. It’s from pre-Jane times. “It is the installation work I made in 2001 for my graduation at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. A mattress in glass formwork. I had taken the cover off the mattress. A body shape could be seen in it, a shape created by intensive use. Very special.”

The mattress was exhibited at the Hague Art Circle, as part of a graphics exhibition. “A man from Missio, a missionary, wrote a poem about it and came up with the idea of turning it into a postcard for Sick Day. There were many negative reactions and also many positive ones. It still reminds some people of the Shroud of Turin.”

It leads to a more principled question that plays a role in more of Margje’s works: “That mattress is typical of everything that inspires me. The human traces, the unintentional memories of using something. I approach Jane this way too. Through all traces, I try to reconstruct her history and personality. What kind of woman is behind the image? Why has she become an icon?”

How long has she been an artist?

In addition to the Royal Academy, Margje has followed more courses. After high school, she first spent a year at the Ecole d’Humanité in Switzerland, Goldern. “Everything I learned there is still reflected in what I do. From creative writing, art history, sculpting, painting, photography, theater to Buddhist philosophy.”

After this preliminary education, Margje studied two years at the Academy for Art and Industry in Enschede and a year of psychology at the University of Amsterdam. She moved to The Hague for the Photo Academy, which was still at the Tarwekamp. “There I was told by a teacher that they could not give me what I needed. I finished the year in the printmaking workshop of the Royal Academy of Arts and studied for another three years in the printmaking, drawing and painting department, where I eventually graduated.” Inspired by the life story of Jane Morris, Margje obtained a diploma from the Writers Academy where she took the modules Novels and short stories.

What is her experience of art life?

“It’s fun to work behind the scenes. After graduating from the KABK, I worked at Theater Zeebelt, a workshop for experimental theatre. Artists, musicians, dancers and writers created a tailor-made performance and I helped with the decor and technology. Later I worked as a volunteer at Galerie Atelier Herenplaats in Rotterdam, an art academy for people with an intellectual disability or psychiatric background. I managed the printmaking workshop and provided guidance in making etchings and linocuts.” Margje has been an artist member of Pulchri for a few years now, where she regularly exhibits and is now a member of the balloting committee. “We are looking for rejuvenation and also want to give space to experimentation and conceptual art.”

Finally, what is her philosophy?

‘God is in the details’. A statement by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. “The work doesn’t stop when the artwork is finished, I also want to send it into the world as beautifully as possible. Every step in the process of creating a work of art is important. Everything must strengthen the image. The order within a series. The photo, title and text. Oscar Wilde said: “I spent all morning putting in a comma and all afternoon taking it out.” I recognize myself in that very much.”

Image 10

Images

1)Marg, the Stain Champion, 2004, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, (photo Sipco Feenstra), 2) Stream of Subconsciousness, 2003, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, 3) Sunlit Studio, 2012, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, (photos Feenstra/Parsons), 4) Honeysuckle, around 1880 (Jane Morris), c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, (photo India Roper-Evans), 5) Seated in the Front Row, 2010, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, 6) A Memory Palace of Her Own, 2011, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, (photo Hein van Liempd), 7) Leaning Backwards in Time, 2016, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, (photo Gerjo te Linde), 8) Decubitus, 2001, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024, 9) Looking for Janey, 2012, 10) Leaving You Behind, 2023, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2024

https://www.reflectionsonjanemorris.com/

https://www.janemorrismuseum.com/

https://www.instagram.com/janemorrismuseum/

https://www.pulchri.nl/nl/kunstenaars/margje-bijl/

https://inzaken.eu/2024/04/25/margje-bijl-in-de-ban-van-jane-morris/

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.