World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 424 - Bas Kwakman

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 424 – Bas Kwakman

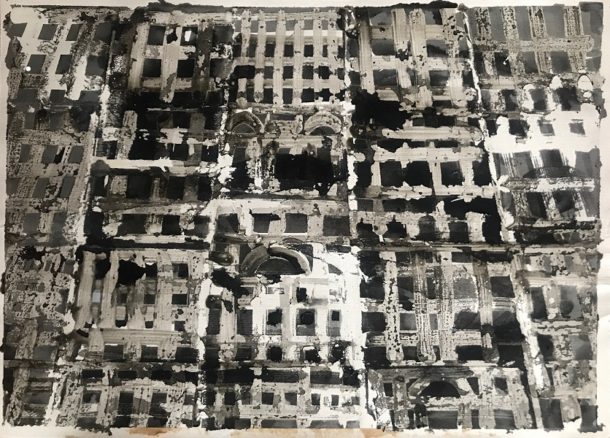

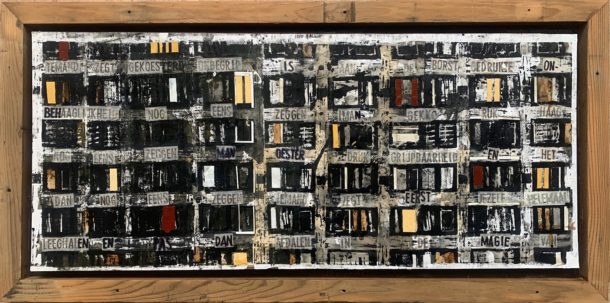

At the Open Studios Borgerstraat in Rotterdam, last May, I saw a number of paintings of a black sooty block of houses. There was no bottom or top, so it could also have been part of an apartment tower. It looked blackened. It looked like a fire had run through it.

I remembered seeing these works before, two years ago at Pulchri, in The Hague. His work – together with that of Edwin Smet – was on display there in the Tape exhibition. Tape was one of the materials both used in their work.

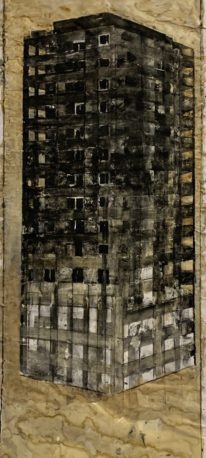

Grenfell Tower

And I also remembered what the black sooty paintings represented: the Grenfell Tower in London, which had caught fire in 2017 and the flat in the Bijlmer where a plane crashed in 1992. Bas Kwakman was happy to tell us more about these paintings and other works.

Some time later I find myself in his studio in one of the side streets of the West-Kruiskade. He shares the anti-squatting space with another artist. I see the paintings on the floor and on the wall, together with other work.

Bas Kwakman: “I remember seeing the images of the Grenfell Tower for the first time. The flat almost burned down. The facades turned out to be clad with highly flammable material. There were social rental homes. I was shocked and impressed by what was left: the structure, the sooty concrete. The residents who had survived wanted to leave the skeleton as a symbol. It has stood that way for a long time. I was intrigued by the story, the shape and the texture. I was looking for a good way to show that appearance.”

He started working with unusual materials: in addition to paint, tape and rubber. “I wanted to create a nice structure, in which the intense story could be found. The paint had to be applied as if it had been on fire, I also used partly rubbed rubber and even coffee stains.”

Special career

Kwakman, trained as a visual artist, has only been active as such for a few years. His special career initially took place behind the scenes of the Rotterdam art world through the RKS (Rotterdamse Kunststichting) and zaal (hall) De Unie, the SKVR (Foundation for Artistic Education). But he was always creative: he made drawings, wrote prose and poetry and even founded a magazine for literature and visual arts in 1997: Tortuca.

That relatively quiet existence changed in a blow in 2003 when he became director of Poetry International, the famous poetry festival. He went on to lead an agency with various employees with an annual multi-day festival in the month of June in the Rotterdam city theatre (Rotterdamse Schouwburg). There was not only the festival, but also the children’s festival, the Poetry Day and Week, the VSB Poetry Prize and the election of the Poet of the Fatherland.

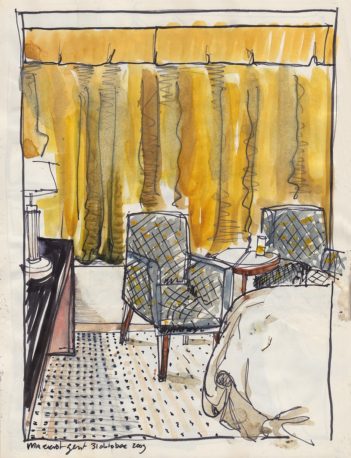

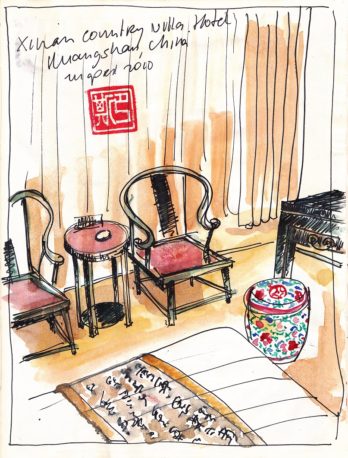

Hotel rooms

He was regularly on the plane to visit festivals and poets in other countries. He went to the famous great poetry festival of Medellin (Colombia), to Mongolia, to South Africa, Norway and many other countries. Every time he came to a new hotel room he had to come to himself and he did that by making a watercolor of his hotel room. In total he made 160 watercolors. I see the watercolors of the rooms in Beijing and Brussels hanging on the wall. They were featured in an exhibition on the occasion of the Poetry Festival of St Andrews, Scotland. He has sold many to hoteliers, acquaintances and friends. Now he has 80 copies left. He also wrote stories about it, illustrated, in the book Hotel Room Stories, also published in Spanish as Historias de habitaciones de Hotel.

Writing and making art again

It was hard work at Poetry, often about 70 hours a week. He ended up working there for 16 years. He agreed with the board not to publish any poetry of his hand. Due to chronic migraine, he stopped in 2019, tried it for a short time in the following year, but then saw that it was better to give a new twist to his life. “I always went for the ‘making possible’, for the ‘creating conditions’, now I wanted to write and take my art seriously again.” He heard skeptical sounds – Sjarel Ex van Boijmans told him: to make art again? You can never do that.” He was also somewhat hesitant about how his poetry would be received by the poet community and his visual work by the art community.

In 2019 he was Writer in Residence in A Coruña, the extreme northwest of Spain, on the Atlantic Ocean. “In a beautiful building on the harbor, modern and classic at the same time with Art Nouveau decoration. There was a closed sheet of glass in front of the buildings, so that it was cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter. You can see it shining from the sea. The city is therefore also known as the glass city, the sparkling city. When you stand in front of the facade, the lines and colors start to mix. I went to investigate that structure. It led to work that formed a second series alongside the Grenfell paintings. In Pulchri both were seen. The exhibition was positively received. It meant my re-entry into the visual arts world. I was 56 then. At that moment I could say: yes, it is possible.”

To his surprise, the art world was open to his work. “I was welcomed with open arms. Every year I do two exhibitions or assignments. I can exhibit. I submitted poems for the Grand Poetry Prize. The jury did not see the names, but the poems. Of the 7000 submissions, a few were published, including both my submitted poems. That was a boost. I was a bit afraid that the poetry world would go crazy if I – former festival director – showed my poems, but that turned out to be a lot better than expected.”

How would he describe the theme of his work?

It consists of three parts: visual arts, prose and poetry. In the visual arts he is concerned with narrative structure, the structure of the paint and the underlying narrative. In prose it’s about the tension between fiction and non-fiction and in poetry about the loneliness of the misunderstood artist.

He explains. He has already told a few things about his visual art, about his prose the following: “I have written five books of things I have experienced and which I have supplemented in favor of literature. That is to say that I have supplemented the non-fiction elements of my diaries with literary resources.” These include Hotel Room Stories (2017), In Poetry and War (2019) and Flankhond (2021). On the wall I see the slogan he received from his Poetry employees “A nice story is better than the truth”. At the moment he is working on a novel with real people. By name and surname. It is set in 1942 in the world of literature, music and politics.

And about his poetry: “It was not clear to me at first, but when I looked at it again I saw that all my poems are about the loneliness of the misunderstood artist. It is about composers, visual artists and poets. Either they were only understood after their death or they were too far from the center. In my poetry I look for a language that is hardly understood. Language that emanates a mystery. It must be fascinating enough, but the reader must not be able to grasp it precisely, then it will start grinding in his / her head.”

Why does he do that?

He points to a painting of a large, gloomy apartment building, with some colors in it, yellow, yellow-white, yellow-orange. A Grenfell-like work. There is a rhythm to the work, and if I look closely I see words in the windows. “The words are part of my poetry cycle Sound Catalogue (Klankcatalogus), in which I describe my love for music. I like extreme free jazz, atonal, noise (thump) music and experimental contemporary classical work. Some works with this theme have hung in Y/OUR Gallery in Rotterdam. I try to bring different disciplines together in this work.”

He feels a lot of affinity with an author who does the same: Georges Perec, especially in the book ‘Life: A User’s Manual’ about the residents of an apartment building in Paris.

Does Bas Kwakman have a key work?

He has, he mentions the following four:

1: Grenfell 1, the first painting he made when he decided to become an artist again, he made it in a rented studio. It hung at Pulchri, where it came out nicely – well lit. “A whole series followed from this work.”

2. Vosje (little fox), a work made at the Academy for Visual Education in Tilburg, where he studied from 1982 to 1987. “Important teachers were walking around: Jan Dibbets, Marlene Dumas, René Daniels. You tried to make work that they liked. It was the Neue Wilden era, everyone made large-format works, including me at first. But it felt like something that didn’t suit me. I didn’t go to the Academy for a month, and in the end I made three very small illustrative literary works. With oil paint. It was literally figurative. With fear and trembling I waited for the response. I received a phone call from director Manders: ‘we are going to assess it’. It hung in a small corner, between the large works. Then I heard from him: ‘Kwakman: you can graduate with this. Just choose a studio in the building. Turn this series into beautiful new work.’ I was flabbergasted, and continued on that kind of work. Among other things, that painting of a little boy with the head of a fox, holding a chair. Title Vosje. It hangs on the wall at my house. This is where it started. It is not good work, but this work is the beginning.”

3. The glass walls of A Coruña, the first step towards the Grenfell paintings.

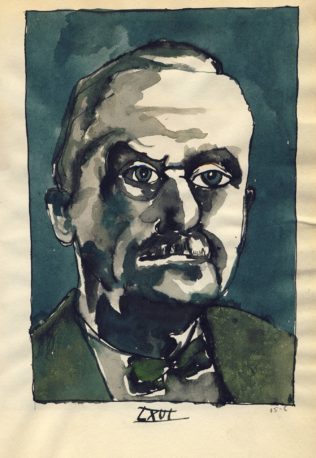

4. The first work I threw a cup of coffee over at the Academy. In several of his works he uses coffee and even coffee grounds. “You get a spot and around that spot you get a line. It’s not a pigment, it’s coffee – all layers remain visible. An eye opener. On the wall he shows some works: a crater in Iceland, with paint and coffee, a rock in Ibiza, Es Vedra, with coffee and coffee grounds. A series of portraits, all made with coffee. He made those portraits at the Academy, portraits of people he admired: Buñuel, Adolf Loos, the architect, and Gustav Mahler. “A colleague jokingly tried what would come up via Chat GPT with the terms Mahler, portrait, black ink, coffee, expressive. It was very much my Mahler portrait.”

How long has he been an artist?

“I graduated from the Academy in Tilburg in 1987. We did that with a club: Art Collective De Mannen (The Men). The four of us shared a studio. The art we made was very diverse, but we stayed together because of the friendship. Immediately after graduating, we had an opportunity to exhibit at the Wolwevershaven in Dordrecht. We could work, live and exhibit there. Everyone went to work in one of the rooms, each based on the designated theme: living room, kitchen, bedroom and children’s room. I started describing and archiving everything. Many people came to the exhibition. The Collective no longer exists – one of the four has died – but we are still good friends.”

Then he went to work behind the scenes. He became project leader and publicity and information officer at the RKS and Zaal De Unie and later project leader and manager at the SKVR (Foundation for Artistic Education Rotterdam).

In 1997 he started Tortuca, a magazine for literature and the visual arts. “I met designer Herbert Verhey. It clicked. It was a magazine in which we could express our love for visual arts and literature. We carefully issued bibliophile booklets for a cherished corner of the bookcase. It was a success though. The first copy was presented in Boijmans. I did it until I started at Poetry. The magazine did continue, eventually 39 issues were published. Wonderful, that combination of prose and poetry with visual art.”

Two years ago he started Kwakman & Smet publishers. “I knew Edwin Smet through Poetry and a poetry festival in Maastricht. He designs books, he is a good visual artist. His work was projected on the back wall of Poetry programmes. When I saw his library at his house, it turned out to be almost the same as mine. Together we exhibited in Pulchri. Then we said: ‘Shall we publish books together?’ The third book has just been published. We have three series: Janosz, Eposz and Peretz.” The first series is about dual artists, who do not opt for one discipline (image or language) but go for both, the second is about merging writers and artists, so that a meeting takes place in the book, and the third series concerns faster editions that respond to current events, such as a book about the relationship between poetry and activism.

Finally, what is his philosophy?

“When I write poetry I am a visual artist and when I work as a visual artist, I notice that the poetry and the narrative are very compelling. That makes me unique. My philosophy: Let me continue with that!”

Images

1) GRENFELL II, 2) A Coruna-as Galerias #8, 50 x 70, GRENFELL VII, 4) Marriot, Ghent, 5) Xinan Country Village – Huangshan, China, 6) Bentleys Stockholm II, 7) Alma Mahler II, 8) Bas Kwakman, photo Wouter LeDuc, 9) SOUND CATALOG # 3, 10) Thomas Mann

https://www.baskwakman.nl/https://www.kwakman-smet.nl/https://ifthenisnow.nl/nl/verhalen/de-wereld-van-de-rotterdamse-kunstenaar-65-bas-kwakman

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.