Does Passion Ignite Perception

Does Passion Ignite Perception

by Mara Lemanis

So many of us have grown up with and then outgrown the division between passion and reason. But early imprinting still urges us to demote one or the other as we set out on our personal course or career, convictions intact.

Hamlet’s cry: “Give me that man that is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him in my heart’s core,” is a great motto for many.

Conversely, in The Mirror and the Lamp, the great critic M.H. Abrams refers to a quote from the 18th c. playwright John Dennis: “The more passion there is, the better the Poetry.” But I admit to having read poems where passion peaks into barbaric yawps.

We’ve been flooded by many therapeutic formulas both to quiet raging passions and skim top-heavy doses of intellection. One of these, especially trendy in today’s culture, is “Mindfulness,” which some objective heads deride as “McMindfulness”–a marketing tool.

In fact the mindfulness technique has proved effective at reducing anxiety and stress in many people, deprogramming harmful emotions and addictive passions. It’s an approach that works. Apparently it’s also a program that has become a commodity.

To Be or Not To Be Mindful

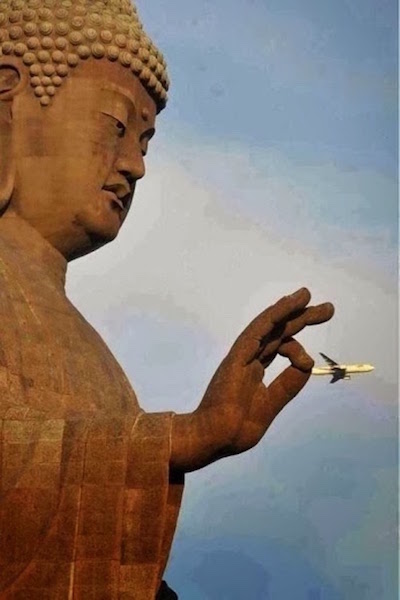

We know it too as a concept birthed through Buddhism. Its original aim was meant to generate unbiased perception of actual events in the world, understanding of one’s own involvement in those events, and compassionate reaction toward all participants, especially those suffering adversity. It underscored exercising compassion for those on opposite ends to one’s own perceptions.

But as practiced in the west mindfulness often glosses over the original Buddhist emphasis on compassion, which welcomes foreign and contrary viewpoints that challenge our personal perceptions. Yet following the western model, it can’t be denied that when we’re less depressed or anxious, or less obsessed, we’re prone to make more room for the anxieties and woes of others.

I think it’s worth reflecting on how compassion swells into passion. Compassion absorbs sympathy for another person’s sensibility and pain and grows into a strong desire to stop the pain. At that point it transforms into empathy; so it

makes sense that strong desire equates with passion. But this is not the common measure.

Compulsion or Passion?

Clinical psychologists distinguish between compulsive passion and voluntary passion. Clearly compulsions are not under one’s control, whereas voluntary passions are engaged in freely.

One of the most valuable insights of Buddhism is how it alerts us to awareness of things in relation to each other, evolving into an awareness of their relative value—prodding us to remember (Smriti) that whatever emotion we experience exists in relation to a mosaic of feelings with either benevolent or noxious outcomes. In remembering, one rises past present-centered, non-judgmental mindfulness toward insights keenly retained. Often this catalyzes a call to ethical action.

In the west mindfulness strives to dispose of prejudices, to foster awareness of the moment—the self present in the moment. But retention and remembering can also stir our attention toward sensory experience. Which doesn’t mean that the sensation we have retained necessarily craves after something. Instead it embraces the experience (anubhavah) of our being in the world, often inspired through the medium of art—music, dance, drama, poetry—and leads us to self-knowledge.

Because this knowledge can come as a sudden insight, its culmination can be enlightenment, self-revelation, even rapture.

Insights Inviting Ecstasy

What elation, for instance, when we evoke the memories of perfumes that suffused our senses as we strolled in a garden full of lilacs, freesias, or honeysuckle, or tread through a forest, inhaling the fragrance of pine. And though the moment of exhilaration is transitory, it unites the self with the natural world. It boosts consciousness.

Mindful memory enables us to freely recall the feeling of blissful attention evoked by strands of music, images in particular paintings, glints of wit and vision released by certain poems and texts. Or the euphoric scent of intimacy when we make love in contrast to the tang of physical contact when we have sex.

Embracing one’s awakened being expresses itself too in the continuous pleasure of work we perform at the peak of our abilities and give to others. In all these ways mindfulness morphs into self-actualization.

The character of self-actualized people is autonomous. They don’t cater to societal approval; they seek fulfillment in purposes beyond themselves. Such people detail many instances of “peak experiences” kindred to a sense of ecstasy and oneness with the universe, sustained within a strong, calm, centered self.

Probably the most dramatic kind of mindfulness beyond ego, involving millions of people, is witnessed in social reform. This is well-documented in the passionate self-sacrifice of persons like Gandhi; Martin Luther King; the civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo, a white woman relentlessly struggling against segregation before she was felled by a gunman. Their biographies are clear accounts of empathy with those made wretched by injustice and detail their passionate efforts to kindle mankind’s humanity.

The passion for reform among such people can’t be reduced to ego drives. They consider themselves as a vehicle to rouse others who are more concerned with personal acquisition, or, for that matter, personal liberation.

Critical Thinking From the Buddha

Here is where the standardized objective of Buddhism—nirvana, which translates to no/not craving—branches off from liberation for oneself (with the rationale that what you do for yourself automatically contributes to others) and grows into the pursuit of liberation for all humanity. And here again, it is persons like Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, born into the caste of untouchables, who launched human rights campaigns for India’s oppressed and later converted to Buddhism; A.T. Ariyaratne, a high school teacher who helmed a grassroots movement to upgrade agriculture, education, and health that was enacted throughout 15 thousand villages in Sri Lanka; and Buddhadasa Bhikku, who initiated “engaged Buddhism” in Thailand, motivating Theravada monks to do actual work in their communities instead of solely cultivating meditative mastery. Many of these adherents have become “Development Monks” in Thailand and Cambodia. They engage in physical as well as spiritual development to reforest and recultivate the environment and foster economic growth without destroying the countryside.

All these movements inspired mindfulness not just beyond ego and passionate avowal but beyond the formal creeds of Buddhism. It was Gautama Buddha himself who warned against accepting his own teachings without first studying, thinking, observing, and investigating before deciding what is true. He strongly advocated freedom of thought and freedom of inquiry. And he invited criticism. Not negation of thought or rationality.

Gautama’s attitude highlights the kind of mindfulness in which attentive thoughts are followed by actions that bear fruit. These percepts rise to a flame of passion that does not burn out but ignites the sense of what it means to bear loving kindness for the world and its people.

Biography: Mara Lemanis has been a teacher and scholar of literature and film at Stanford, Yale, and the Jagiellonian University in Kraków; her essays have been selected for 20th CENTURY LITERARY CRITICISM and are included in undergraduate student textbooks in the U.S.

During her work as an archivist for Historical Preservation she investigated and nominated multiple sites in the Dakotas to the National Register of Historic Places. Among her most interesting studies were those of the Oglala Sioux at Pine Ridge and Wounded Knee where on December 29, 1890 the U.S. cavalry massacred members of the Lakota Nation.

In the course of her work she also took part in the communal spirit of the purification ceremony at a number of Lakota Sweat Lodges.

Recently she has worked with the IRC to assist refugees in Oakland, California.

Her father, Osvalds J. Lemanis, was an internationally renowned Latvian choreographer (The Royal Order of Vasa-Gustav V).

She also writes for the Diplomat Magazine in The Hague.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Mara Lemanis alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Mara Lemanis and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.