World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 286 - Georgia O’Keeffe

World Fine Art Professionals and their Key-Pieces, 286 – Georgia O’Keeffe

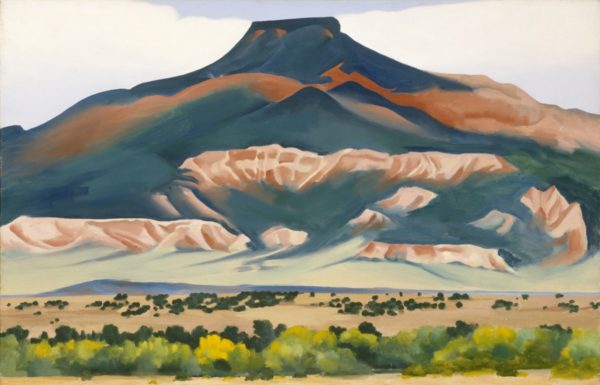

We know Georgia O’Keeffe from the paintings of New York skyscrapers, enlarged flowers and especially the landscapes and animal skulls of New Mexico.

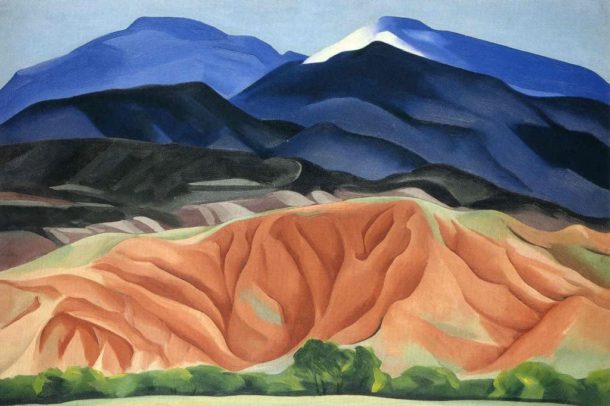

In 1929, the American painter travelled to New Mexico with her painter friend Rebecca Strand. They stayed in Taos in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains at the home of Mabel Dodge Luhan, who gave them a studio.

Rocks and bones of the desert floor

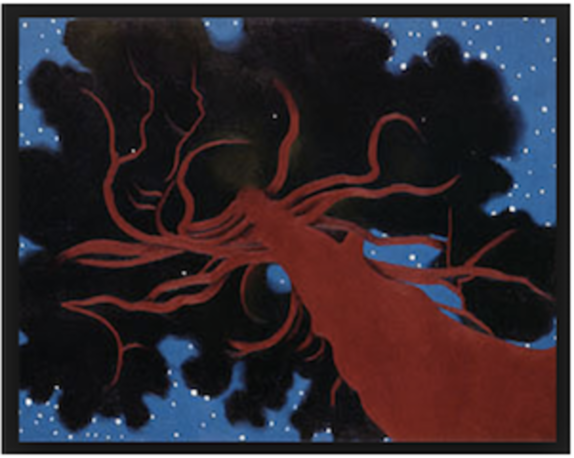

From her room she had a clear view of the Taos Mountains and the morada (meeting house) of the Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno or the Penintentes. O’Keeffe took many trips, exploring the rugged mountains and deserts of the region that summer and later visited the nearby DH Lawrence Ranch where she completed her famous oil painting The Lawrence Tree.

From then on she went to work in New Mexico almost every year. She collected stones and bones from the desert floor and made them, together with the typical architectural and landscape forms of the area, the subject of her paintings. A true loner, O’Keeffe explored her beloved region in a Ford Model A. In 1936, she completed what would become one of her best-known paintings, Summer Days. It shows a desert scene with a deer skull with vibrant wildflowers. Resembling Ram’s Head with Hollyhock, she depicted a skull floating above the horizon.

Sun Prairie

Georgia O’Keeffe was born on November 15, 1887, on a farm in the town of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. She was the second of seven children. When she was ten she had decided to become an artist. Together with her sisters Ida and Anita, she took drawing and painting lessons from the local watercolorist Sara Mann.

It all started in earnest at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905 and then the Art Students League of New York. The classes focused on copying what was in nature, when she actually wanted to get more of the essence. In 1912 she came into contact with the principles and philosophies of Arthur Wesley Dow, who created his work based on personal style and interpretation of subjects, rather than copying or representing them. Dow’s approach was influenced by principles of Japanese art regarding style and composition. O’Keeffe began to experiment with abstract compositions and developed a personal style that departed from realism.

Alfred Stieglitz

This caused a major change in the way she thought about and approached art. In 1915 she completed a series of innovative charcoal abstractions based on her personal sensations. O’Keeffe mailed the charcoal drawings to a friend and former classmate at Columbia University Teachers College, Anita Pollitzer, who showed them to Alfred Stieglitz in his 291 gallery in early 1916. Stieglitz felt they were the “purest, finest and most sincere things he had seen in a long time”, and said he would like to exhibit them. In April of that year, ten of her drawings were on display at gallery 291.

O’Keeffe moved to New York in 1918 at the request of Stieglitz and began working seriously as an artist. Stieglitz, twenty-four years older than O’Keeffe, provided financial support and arranged a place to stay and a studio for her in New York in 1918. As he promoted her work, they developed a close personal bond. She became acquainted with the many early American modernists who were part of Stieglitz’s artist circle. Among other things, Paul Strand’s photography, as well as that of Stieglitz, inspired O’Keeffe’s work.

Private sensations and feelings

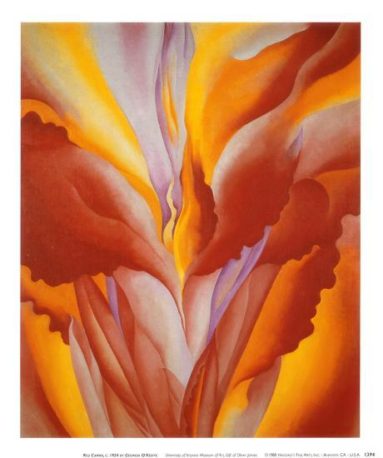

O’Keeffe wanted to express her most personal sensations and feelings. Instead of starting with a sketch before painting, she went straight to work. In the mid-1920s she made about 200 flower paintings. They were huge flowers, including oriental poppies and various red canna paintings. They seemed to be viewed through a magnifying glass. She painted her first large-scale flower painting, Petunia, No. 2, in 1924, which was first exhibited in 1925. On November 20, 2014, O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1 (1932) sold in 2014 for $ 44,405.000. at an auction by Walmart heiress Alice Walton, more than three times the previous world record at auction for a female artist. Meanwhile, Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were married in 1924.

Many thought the Red Canna paintings looked like female genitalia, but O’Keeffe denied that was the case. The reputation of portraying women’s sexuality was also fueled by explicit and sensual photographs that Stieglitz had taken and exhibited of O’Keeffe.

Skyscrapers

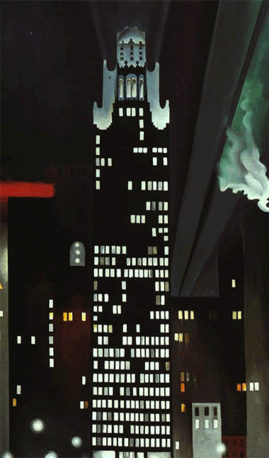

After moving into an apartment on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel in 1925, O’Keeffe began a series of paintings of the city’s skyscrapers and skyline. In 1928 she made a cityscape, East River, from the thirtieth floor of the Shelton Hotel, it was a view of the East River and the plumes of smoke from the factories in Queens. The following year, she made her last skyline and skyscraper painting in New York City. She traveled to New Mexico, which, as we have seen, became a great source of inspiration.

O’Keeffe did not work from the late 1932 until about the mid-1930s, when she had several nervous breakdowns and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She got these nervous breakdowns when she heard about an affair of her husband.

Hawaii

Recovered in 1938, she accepted an invitation to go to Hawaii, also to paint a pineapple plant for a pineapple canning company. She also had the opportunity to document other Hawaiian subjects. By far the most productive and vibrant period in Hawaii was in Maui. She painted flowers, landscapes and traditional Hawaiian fish hooks. Back in New York, O’Keeffe completed a series of 20 sensual green paintings. However, she didn’t paint the requested pineapple until the Hawaiian Pineapple Company sent a plant to her New York studio.

In the 1940s O’Keeffe had two retrospectives, the first at the Art Institute of Chicago (1943). Her second was in 1946, when she was the first female artist to have a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan.

Abiquiú

After Stieglitz’s death in 1946, she lived permanently in New Mexico at Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio in Abiquiú, until the last years of her life when she lived in Santa Fe. After her death in 1986, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was established in Santa Fe.

Although feminists celebrated O’Keeffe as the founder of ‘female iconography’, O’Keeffe refused to join the feminist art movement or collaborate on projects that were exclusively women. She didn’t like being called a ‘female artist’ and wanted to be considered an ‘artist’.

Images

1) Ram’s Head with Hollyhock, 2) The Lawrence Tree, 3) Petunia, No. 2, 4) Jimson Weed / White Flower No 1, 5) Red Canna, 6) cityscape & skyscraper painting, 7) pineapple bud, 8) Black Mesa Landscape, 9) Abiquiú, 10) Georgia O’Keeffe

https://ifthenisnow.eu/nl/personen/georgia-okeeffe

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.