World Artists and their Story, 46 - Leonardo da Vinci

World Artists and their Story, 46 – Leonardo da Vinci

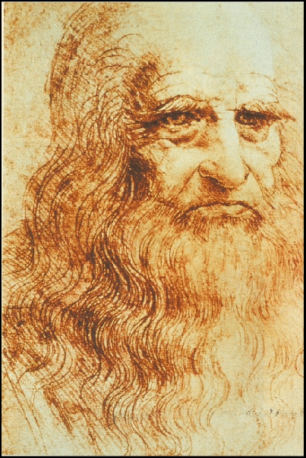

Leonardo da Vinci is a multi-talented uomo universale. He mastered various disciplines such as sculpture, drawing, music and painting. The last discipline was the pinnacle of the arts, according to Leonardo.

He is best known for his painting, but also calls himself an engineer, architect and scientist. The knowledge that was initially useful for painting becomes for him an end in itself. His fields of interest are many: optics, geology, botany, hydrodynamics, architecture, astronomy, philosophy, acoustics, physiology and anatomy. But he was also a musician and organizer of parties.

Ten godfathers

He is the result of an illegitimate romantic relationship between a peasant woman, Caterina di Meo Lippi, and a notary, Pierre da Vinci. He is baptized the Sunday after his birth. The ceremony takes place in the church of Vinci by the pastor, in the presence of notables of the city and important aristocrats of the area. Ten godfathers – an exceptional number – all from Vinci, bear witness to the baptism.

Until he was ten, 1462, he grew up with his paternal grandparents in the family home of the Vinci family. In Florence, his father enrolls him in a “school with abacus” where he learns the principles of reading, writing and especially arithmetic, and then in the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio, where Botticelli and Domenico Ghirlandaio also roam.

Chiaroscuro

Like all newcomers to the studio, he starts out as an apprentice. He is allowed to clean brushes, prepare material for the master, sweep floors, grind pigments and take care of preparing varnishes and glues. Gradually he is allowed to transfer the master’s sketch to the panel. Then he becomes a companion. He may make decorations and paint the decor or landscape. Things are going well and after a while he can do whole parts of the work.

He discovers the ancient technique of chiaroscuro which consists of using contrasts of light and shadow to create the illusion of relief and volume in two-dimensional drawings and paintings. While learning to create colours, he experiments with mixing pigments with large amounts of transparent liquids to obtain translucent colors and thus model the gradations of draperies, faces and trees.

“Open your eyes”

Leonardo was not raised by his parents: his father lived mainly in Florence and his mother took care of the five other children she had after her marriage. His uncle Francesco, 15 years his senior, and his paternal grandparents take over his upbringing. Thus, his grandfather Antonio, a passionate sloth, gives him a taste for observing nature. He constantly repeats “Po l’occhio!” (“Open your eyes!”). His grandmother is also close to him: she is a ceramist, and it is probably she who introduces him to art.

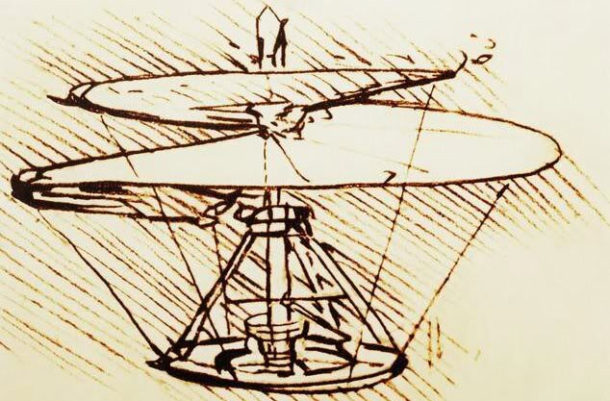

However, he has neither the training nor the research methods of a scientist. His lack of university education, however, frees him from the academicism of his time: he claims to be a “man without letters” and advocates practice and analogy. With the help of some scientists, he begins writing scientific treatises, accompanied by explanatory drawings.

The Duke of Milan

He left the Verrocchio atelier in 1482 and presented himself as an engineer to the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. Sforza sees something in him. At court he gets a few painting assignments. He starts working in a workshop where he also studies mathematics and the human body. He meets Gian Giacomo Caprotti, better known as Salai, a ten-year-old child, a turbulent boy, whom he takes under his wing.

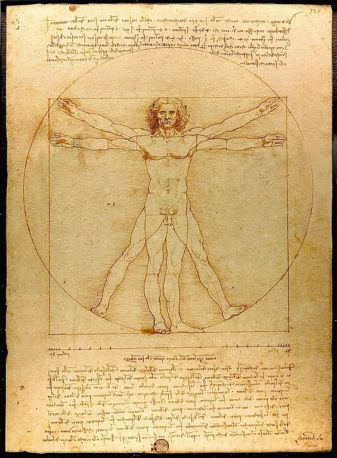

During this time, Leonardo devotes himself to technical-scientific studies, it ranges from anatomy, mechanics (clocks and looms) and mathematics (arithmetic and geometry). He notes it meticulously in his notebooks, where he also makes drawings. In 1489, he begins a book on human anatomy. This led to the ‘Vitruvius Man’, which he draws based on the writings of the Roman architect and writer Vitruvius.

Organizer of parties and shows

He becomes “organizer of parties and shows” that were given in the palace and invents successful theater machines. The pinnacle of his achievements, dating back to 1496, is a masterpiece where the protagonist is transformed into a star. He is active as an engineer, but has to do his best to get this recognised. The plague epidemic in Milan of 1484-1485 is for him an opportunity to propose solutions to the theme of the “new city”. In 1487 he takes part in a competition for the construction of the lantern tower of the Milan Cathedral and presents a model in 1488-1489.

La Dame a l’ermine

Between 1489 and 1494, he is also responsible for creating an imposing equestrian statue in honor of Francesco Sforza, Ludovic’s father and predecessor. He plans to make a moving horse first. But despite the difficulties of such a realization, he has to give up and return to a more traditional solution. The clay model is on display in the Sforza Palace and contributes significantly to Leonardo’s notoriety at court. He was appointed to carry out various works on the palace, including the heating system and some portraits. During this period he painted the portrait of La Dame à l’ermine (1490), a portrait of a Milanese lady. Another commission is the famous fresco The Last Supper, executed in the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

La Joconde

In September 1499 Leonardo leaves for Mantua and Venice. He still paints and dedicates himself to both architecture and military engineering. For a year he made geographical maps for César Borgia. In October 1503 he is back in Florence: he joins the Guild of Saint Luke – the painting company in the city and starts working on the portrait of a young Florentine woman named Lisa del Giocondo. The painting was commissioned by her husband, the wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. Completed in 1513/1514, the portrait has since been known as La Joconde, and to the general public as the Mona Lisa.

The Human Anatomy

The French are temporarily in power in Milan. The King of France, Louis XII, summons him to Milan, where he is the monarch’s ‘painter and engineer’ from 1506 to 1511. He meets Francesco Melzi, his student, friend and performer. In 1504 his father dies, but he is excluded from the will. In 1507 he becomes usufructuary of the land of his deceased uncle. After completing the painting of The Virgin on the Rocks on October 23, 1508, Leonardo gives up his profession of painter to become a researcher and engineer and paints only seldom: a Salvator Mundi perhaps, but whether that work really belongs to him remains to be seen.

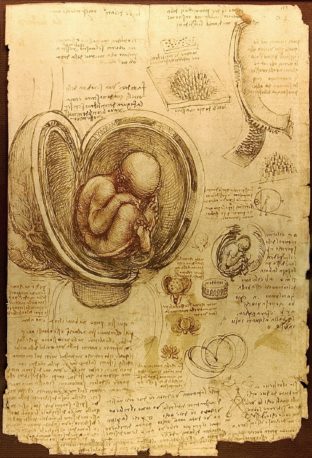

Around 1509 he continued his studies on human anatomy. He studies the genitourinary system, the development of the fetus, the human circulatory system and discovers the first clues to the process of arteriosclerosis.

Pope Leo X

In 1514 Leonardo goes to work for Giuliano de Medici in Rome. Giuliano is the brother of Leo X, the Pope. Leo X is an aesthete and bon vivant who likes to surround himself with artists, philosophers and men of letters. Leo X and Giuliano are the sons of Lorenzo de Medici, Leonardo’s first benefactor when the painter was still in his infancy in Florence.

Leonardo puts painting aside altogether and starts working on a project to drain the Pontine swamps. Leonardo is allowed to work in the Belvedere Palace, the summer palace of the Popes that was built thirty years earlier. There he finds the books and paintings he had left in Milan and sent to Rome. The palace gardens allow him to study botany and are also the setting for jokes he loved.

Died in France

In 1516, François I, King of France, invites him to France at the manor of Cloux with Francesco Melzi and Salai. He takes the Mona Lisa and completes it there.

In 1519 Leonardo was 67 years old. Feeling that his death was imminent, he had his will drawn up at a notary in Amboise on 23 April 1519. He died in 1519 in Clos Lucé. His friend Francesco Melzi inherits his paintings and his notes. He shares with Salai the vines that Leonardo received from Ludovic Sforza.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and positions expressed within this guest article are those of the author Walter van Teeffelen alone and do not represent those of the Marbella Marbella website. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to Walter van Teeffelen and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.

The opinions expressed by individual commentators and contributors do not necessarily constitute this website's position on the particular topic.